The Rearview Mirror: Studebaker Kills Packard

This week in automotive history is a sad one. For this week in 1958, the Packard brand is terminated by the Studebaker-Packard Corp.’s board of directors without an official vote.

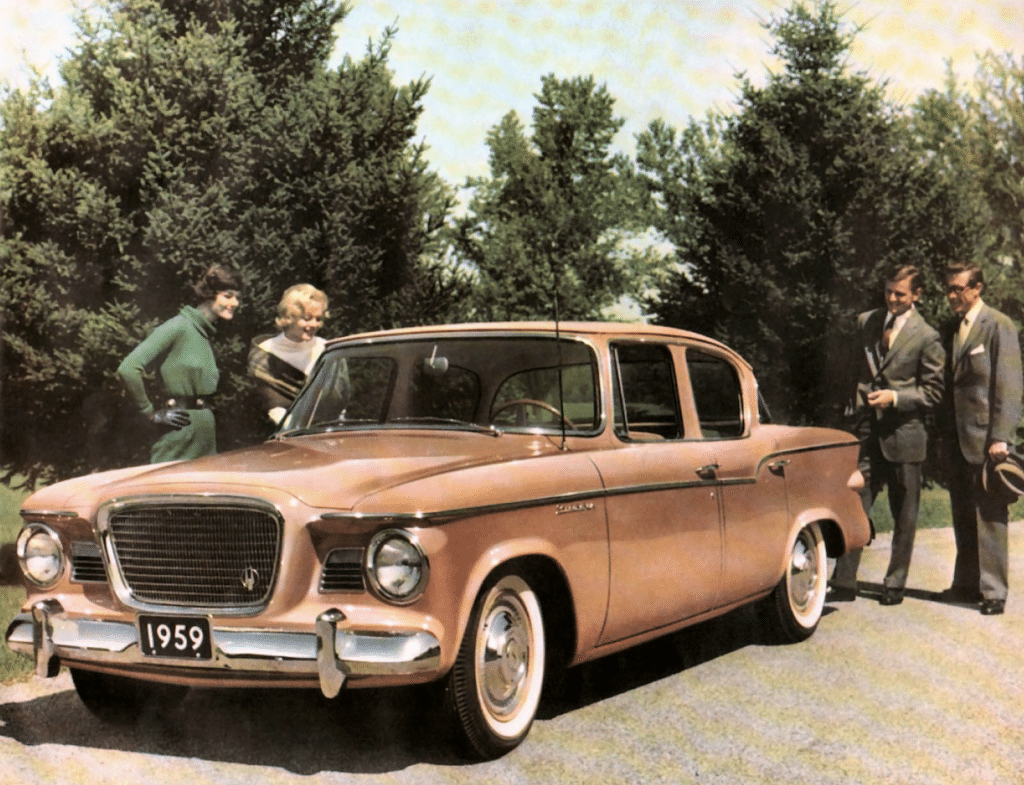

The move comes from a proposal by Studebaker Chairman Harold E Churchill. The money saved will be redirected by the troubled company’s hail Mary pass: the introduction of a new compact car for 1959, the Studebaker Lark.

A legendary automaker outlasts its peers

It is said Packard was a car built by gentlemen for gentleman. Its slogan, “Ask the man who owns one,” was unchanged for decades, a reflection of its position as the luxury car of choice among old money types.

Packard was the only independent American luxury line left after World War II. The Depression killed off two of what were known as the “Three Ps,” Packard, Peerless and Pierce-Arrow, as well as Duesenberg and Marmon. The company had managed to survive by building its lower-priced Clipper models for the mid-price market segment, a clear step away from its concentration on luxury automobiles.

This led to the company selling almost 105,000 cars in 1949, nearly breaking a company record. But many historians feel the company should have shuttered its lower cost lines after the war, which would have made the company more profitable, particularly in the postwar sellers’ market.

It didn’t happen. Instead, a series of strategic errors led to its downfall.

Management loses its way

Before the war, Packard Chairman Alvan Macauley made a crucial blunder. Although the company was renowned for manufacturing some of the finest bodies in America, Macauley decided to farm out body development and manufacturing to Briggs Manufacturing to save money starting in 1940. The savings proved elusive as Briggs started to raise their prices, eventually costing Packard more than it would to build the bodies in-house.

Macauley retired in 1948, turning over control of the company to George Christopher, an ex-General Motors executive who helped ramp up Packard production for its medium price cars. The man didn’t know the difference between mass production and class production. But Christopher left a year and a half later, and was replaced by Hugh Ferry, a man more interested in finding his own replacement than preparing the company for the future.

He found his man in James Nance, a former Hotpoint appliance executive with no automotive experience. He came on board in 1952, separating the lower-priced Clipper into its own brand, and commissioning formal sedans and limousines from coachbuilders Durham and Henney. But soon, he faces his first real crisis. In 1952, Chrysler Corp., Briggs’ biggest customer, buys the company, agreeing to supply Packard bodies through 1954.

In response, Nance decides to move operations from Packard’s old two-story East Grand Boulevard plant to a former Chrysler plant, the smaller, single story Conner Avenue plant.

A doomed merger

The move occurred as Nance was looking to merge with another automaker to help combat the Big Three automakers. This led to a marriage with Studebaker. The merger made sense on paper. Neither company competed in the same market segments, and platform sharing could save time and development costs for new models.

But Nance didn’t thoroughly examine the books before the merger, or he would have known what Studebaker executives already knew, and Packard analysts discovered after the merger: Studebaker’s outdated facilities and pampered union workforce contributed to an overhead that would take an annual production of 300,000 units just to break even, a number it never came close to reaching after 1951.

Nance was mortified to discover that Studebaker was in worse shape than Packard. This would lead to the company shelving a plan to develop a common vehicle architecture.

Instead, Packard’s aging products were updated for 1955. But the company’s move to the single-story Conner Avenue plant led to massive quality issues. The new plant was one-fifth the size of the old one.

The lack of space and crammed working conditions led to poor quality, something unheard of in a Packard — which was known for its high quality. A new V-8 and ultra-drive automatic transmission, both developed in house, also had issues.

It was compounded by Nance’s insistence that more parts be produced in house, rather than obtained from suppliers. But this further reduced profits. The company had a reciprocal purchasing agreement with American Motors Corp. When Packard stopped buying parts from AMC, AMC stopped buying Packard V-8s.

A new sheriff in town

By early 1956, Studebaker-Packard was bleeding money, and the U.S government was concerned. Studebaker had been a major military supplier since the Civil War, and the government wanted Studebaker to survive.

In May 1956, Curtiss-Wright, a massive aviation company, supplied the operating capital, and began calling the shots. Nance was not amused, and decamped to Ford Motor Co., where he became vice president of the Mercury Edsel Lincoln Division.

Curtiss-Wright went to work, closing Packard’s pants, selling its proving grounds and moving Packard production to Studebaker’s South Bend, Indiana plants.

But the Packards that resulted were merely badge-engineered Studebakers; the cars fooled no one, particularly Consumer Reports.

In its 1957 annual auto guide, the magazine said that Studebakers were poorly built and “burdensome to drive.” Similarly the Packard Clipper, little more than a Studebaker President with Packard trim came in last among its price group, not surprising given what the magazine thought about Studebaker.

With dealers dwindling along with sales, the inevitable happened, and this week 64 years ago, the once-proud Packard name became a part of history. In another eight years, so would Studebaker.

Auto Lovers Land

Comments

Post a Comment