The Rearview Mirror: Triumph of the Bean Counters

This week in 1982, General Motors introduces the J-Cars, aka the Chevrolet Cavalier, Pontiac J2000, Oldsmobile Firenza, Buick Skyhawk and Cadillac Cimarron — the first cars ever designed by GM to be shared across all of its divisions.

But GM’s first subcompact front-wheel-drive automobiles were emblematic of deep problems at the world’s largest automaker, ones that would eventually lead to its bankruptcy.

But like all such stories, the real beginning of the J-Cars can be traced back to 1956.

Too successful

It’s 1956, and General Motors holds a 50% U.S. market share, manufacturing one of every two cars sold in America. When Henry Ford commanded 60% the U.S. market in 1921, there were dozens of American automakers.

Even by the end of World War II, there were 10 major carmakers. But within a decade, there five with GM, Ford and Chrysler accounting for 94% of sales. That was the year that the idea of dismantling General Motors first entered the mind of Stanley Barns, an assistant attorney general with the U.S. Justice Department’s antitrust division. Years would pass while the case was assembled, but by 1967, a draft lawsuit alleging GM of breaking antitrust rules was published by The Wall Street Journal.

One thought was to break off Chevrolet, which accounted for roughly half of GM’s sales. But by then each division’s manufacturing had been amalgamated into General Motors Assembly Division, or GMAD, making any breakup of the company impossible as splitting off Chevrolet left it without any manufacturing.

Ultimately, GM was not broken up, and GM’s market share of the American car market rose to 62.6% by 1980.

Trouble at the top

Ultimately, the rise of GMAD also coincided with the dominance of bean counters at GM, passionless men who cared about profits, not cars. Certainly that wasn’t the case of longstanding Chairman Alfred Sloan, who carefully led the construction of a price ladder of brands that started with Chevrolet, and got rose through Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Buick, topping off with Cadillac.

But Sloan, made a crucial mistake after stepping down as Chairman of General Motors in 1956, backing Fred Donner for the top job at General Motors in 1958 rather than GM’s President and CEO Harlow Curtice.

Donner was a heartless financial specialist who knew little about cars, having spent his career in GM’s New York City-based financial office. Under Donner, GM increased the number of parts shared across GM divisions, as this reduced costs. Slowly, the differences that had once distinguished a Pontiac from a Buick vanished. Donner didn’t understand that these differences mattered to customers.

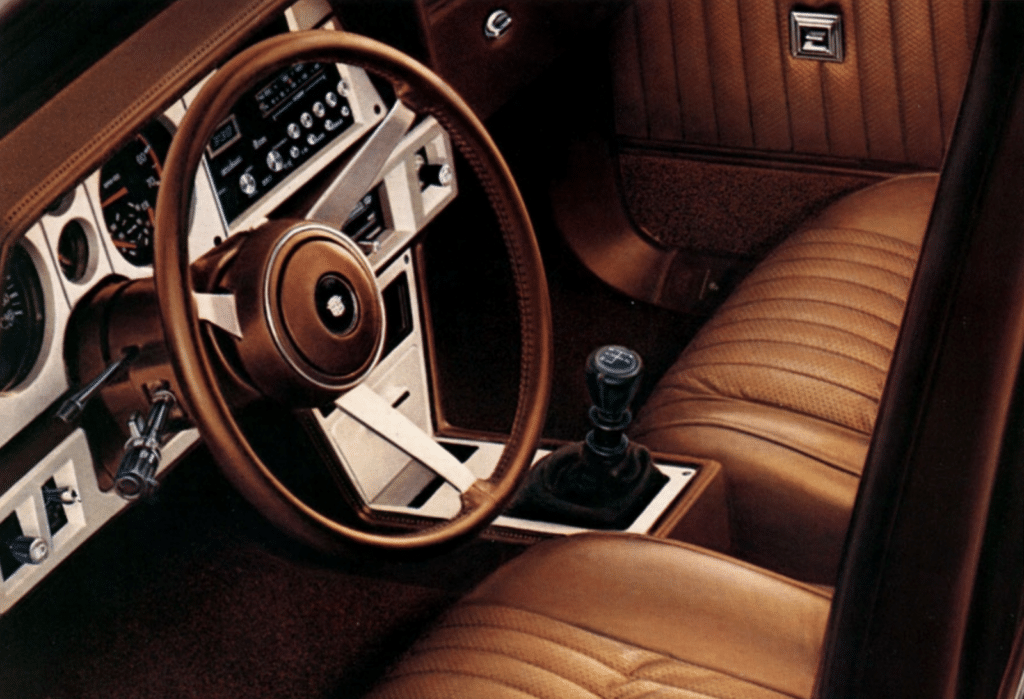

As the bean counters continued to run GM, they centralized product development under platform teams, taking the responsibility away from its divisions. Increasingly, those at the top dictated sharing platforms and outer sheetmetal, with little to differentiate the different cars aside from the grille, taillamps and badges.

Then, in 1977, GM’s Vice President of Design, Bill Mitchell, retired. He was replaced by Irv Rybicki, whose talent was administration, and whose gentle nature was the antithesis of Mitchell’s. Under Rybicki, GM Design atrophied as design became subservient to engineering and manufacturing — something never true at GM.

A Design Dud

Bean counters loved badge engineering, as it proved profitable. It reached its peak in 1982, when GM introduced the midsize A-Body cars, the internal designation for the Chevrolet Celebrity, Pontiac 6000, Oldsmobile Cutlass Cierra and Buick Century, which Fortune magazine lined up for a cover shot. While GM had been shared platforms and bodies since 1932, it had never been so glaringly obvious. And it would followed by the most egregious example: the subcompact J-cars, the first time that GM used the same car for all five divisions.

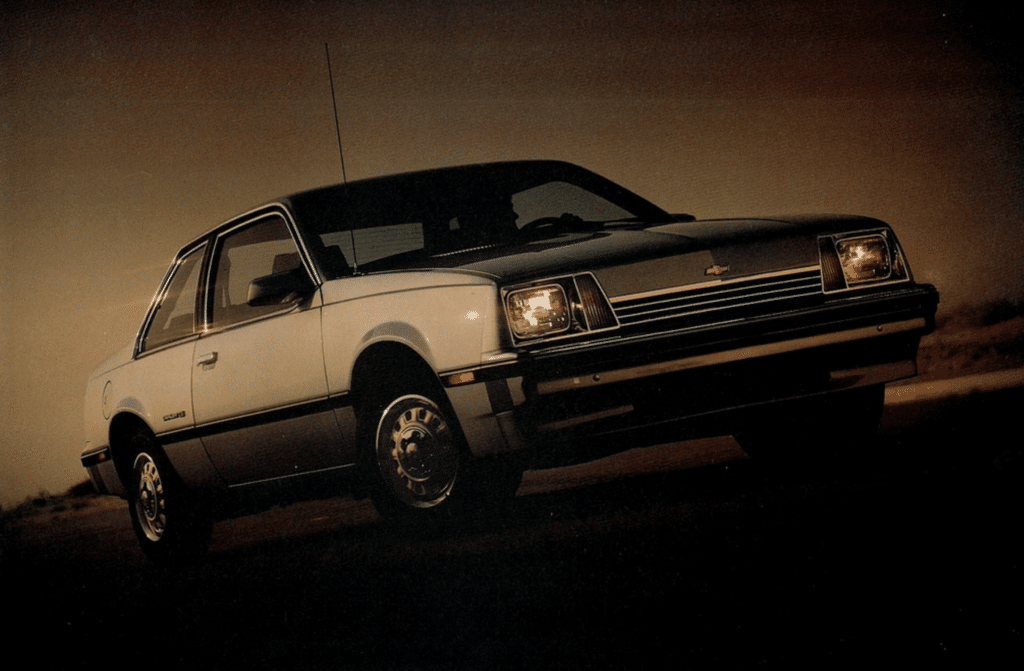

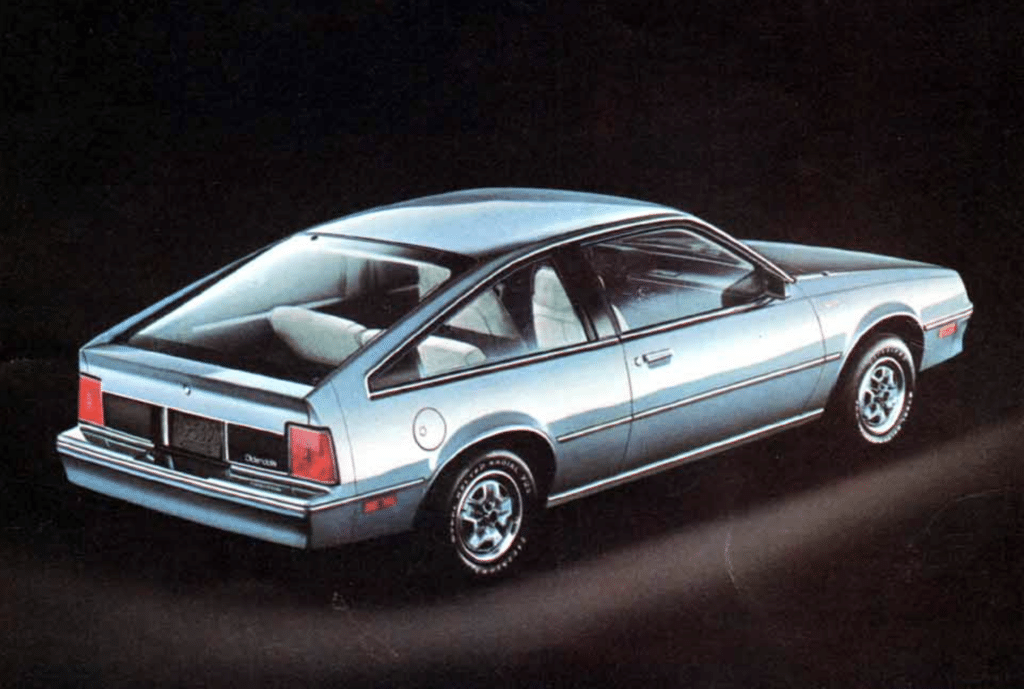

Arriving as the Chevrolet Cavalier, Pontiac J2000 (later the Sunbird), Oldsmobile Firenza, Buick Skyhawk and Cadillac Cimarron, they were meant to challenge the rising tide of small, affordable, reliable Japanese cars. But the 88-horsepower 1.8-liter 4 cylinder was underpowered compared to its competitors.

It’s not that GM didn’t have alternatives, they did. One was an overhead-cam mill built by Opel. But Chevrolet engineers designed their own overhead-valve engine, which proved less expensive to build. They also reused parts from the larger X-Cars, aka the Chevrolet Citation, Pontiac Phoenix, Oldsmobile Omega and Buick Skylark. But because they were engineered for a larger car, the parts added needless weight, exacerbating its lack of power. It took a painful 14 seconds to run 0-60 mph.

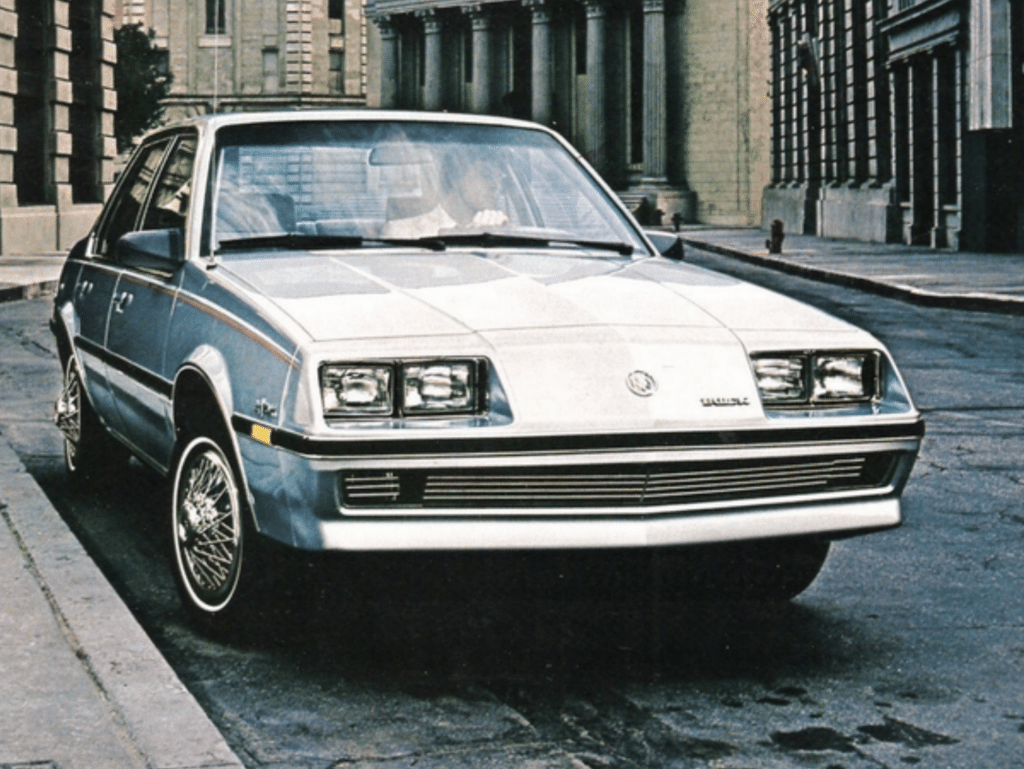

Worse, they were overpriced. At a time when a Honda Civic started at $5,154 and the Toyota Corolla started at $5,448, the Chevrolet Cavalier started at $6,966. And upon it launch, GM built fully loaded versions, making a Chevrolet Cavalier some $2,500 more than a comparable Honda Accord. Needless to say, the Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac J-Cars were slow sellers.

But what’s worse is what the cars did to GM’s brand equity. Why would anyone buy a Cadillac when it was identical to a Chevrolet with the exception of its badge?

It would take more badge-engineering, and a couple decades of inept decisions made mostly by bean counters to push GM into bankruptcy.

And while Chevrolet sold many Cavaliers and Pontiac the same with J2000s, one wonders how much their poor engineering led customers to buy a Honda or Toyota for their next car.

Given that GM’s 2022 market share is 17%, you know the answer.

Auto Lovers Land

Comments

Post a Comment